- 23 August 2025

- No Comment

- 973

The Business of Blood: How a Life-Saving Fluid Became Big Pharma’s Cash Cow

Blood keeps us alive; plasma, the pale, protein-rich liquid part of blood, keeps many patients alive. Yet behind the lifesaving narrative there’s a quieter, darker market where plasma is bought, processed and resold as extremely profitable medicines. This investigative piece pulls apart that market: how plasma is collected, who profits, which risks are pushed onto donors, and why the world has become dependent on a commodified body fluid harvested mostly from the vulnerable.

What is Plasma and Why Blood Plasma is Called “Liquid Gold

How Plasma Donations Work

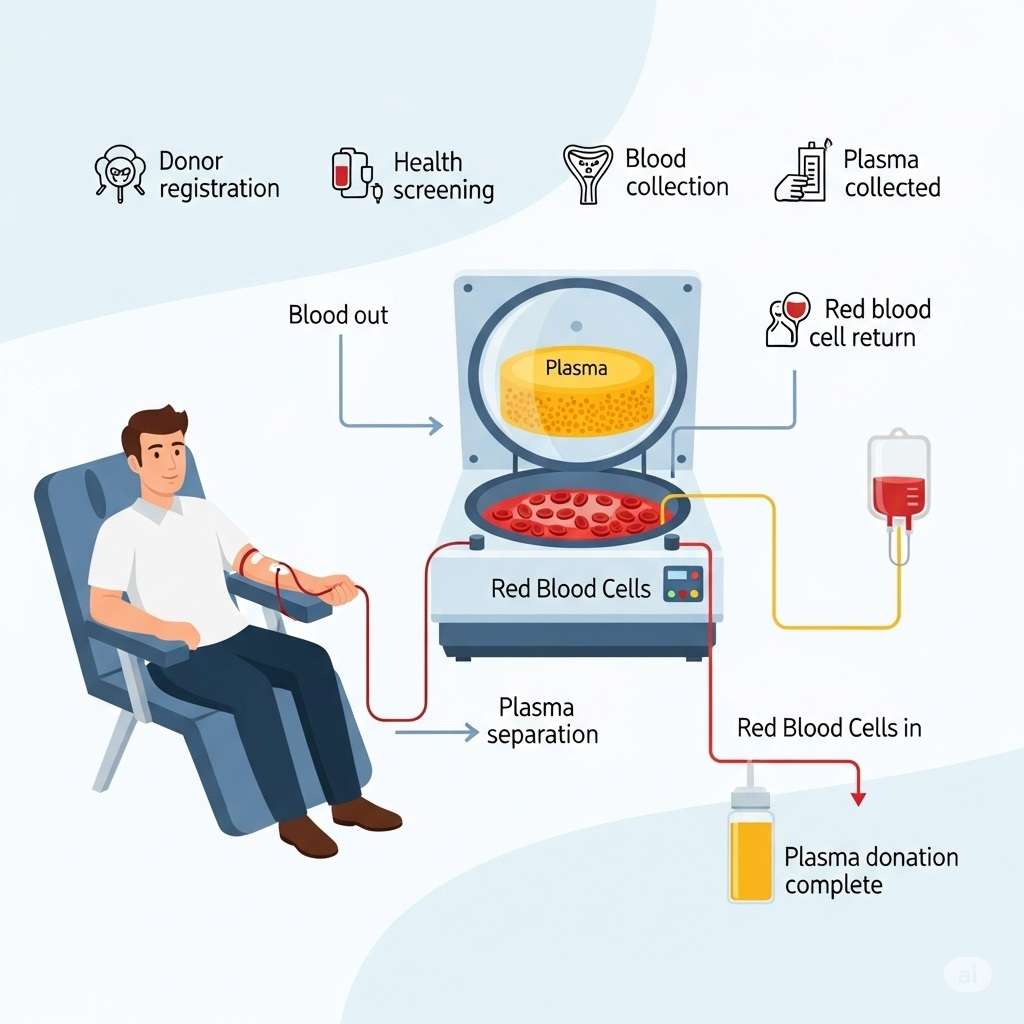

Most people imagine blood donation as a one-off, altruistic act — a pint given to help another human. That’s only part of the picture. Whole blood can be separated into red cells, platelets and plasma. Plasma contains essential proteins used to manufacture a class of high-value biologic medicines that treat hemophilia, immune deficiencies and other serious conditions and often called as liquid gold.

Plasma donation (apheresis) differs from whole-blood donation in one crucial way: the machine separates and keeps the plasma, then returns the donor’s red cells and platelets. Because the body replenishes plasma relatively quickly, many U.S. centers permit donors to give plasma far more often than whole blood — in some cases twice a week. That frequency, combined with steady cash payments, turns plasma into a repeatable income stream for donors and a steady raw material stream for companies.

From Donor to Drug — How Plasma Becomes Medicine

The Profit Pathway of Plasma-Derived Drugs

The proteins isolated from plasma — immunoglobulins, clotting factors and others — are concentrated, purified and processed into branded drugs such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and factor replacement therapies for hemophiliacs. These products offer real therapeutic benefit, but the path from donor chair to pharmacy shelf also creates enormous profit margins for the companies that control the processing, packaging and distribution.

Paid Plasma: Economics, Incentives and the Moral Fault Lines

A Controversial Market Centred in the United States

Most countries prohibit paying people for plasma. The exceptions include Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Germany and critically — the United States. The U.S. dominates the paid plasma market: a large share of the world’s spare plasma originates from compensated donors in America. Donors are typically paid modest sums per visit — commonly in the $30–$50 range — which for many people becomes an essential part of their monthly income.

That payment creates ethical friction. Selling hair or sperm may be socially acceptable; selling plasma sits in a grey zone.

When payment is needed to pay rent, utilities, or feed a child, the “choice” to donate starts to look less voluntary and more coerced by economic necessity.

Why Economic Desperation Matters

Financial shocks — notably the 2008 crisis — pushed many people toward plasma centers as a reliable side income. For someone with few options, two chairs a week (and the attendant $200–$400 a month) is a lifeline. But the human cost can be high: donors report fatigue, dizziness, dehydration and in extreme cases fainting and blackouts. When money is at stake, donors may underreport symptoms or medical history to keep qualifying. The result is a system that monetizes vulnerability — exactly the population least able to absorb the health risks.

Human Stories: the Blurred Line Between Consent and Necessity

The human side of this market is revealed through personal stories and investigative reporting. Some donors have reported experiencing fatigue, health issues, and other problems after donating, yet they continue due to financial necessity. Others have resorted to extreme measures to pass screening requirements or lied about their medical history. In some cases, donors’ plasma cards are even used as a form of payment or collateral. These stories highlight a broader issue: when financial incentives are high and screening relies on self-reporting, it can create significant risks for both donors and patients receiving plasma-derived treatments.

Screening, Safety and Corporate Self-Interest

What Screening Looks Like — and Where it Falls Short

First-time donors typically get a full physical and blood screening. Repeat donors, however, often see little more than a digital questionnaire, a quick check of blood pressure, hematocrit and protein levels, and then the needle. That tradeoff — speed and volume for depth of screening — is profitable for clinics but risky for public health.

Industry defenders point out that plasma destined for medicines undergoes intensive treatment and testing, and that paid plasma is not used directly for transfusions. Those are true safeguards. But critics argue that insisting on minimal donor oversight and avoiding stricter screening protocols is partly driven by an unwillingness to scare away the very donors the industry depends on. In other words, tightening safety measures could shrink the donor pool and undercut bottom lines.

Past Scandals that Should Warn Us

History provides grim lessons. In the 1980s, blood products contaminated with HIV infected hundreds — particularly hemophiliacs who depended on clotting factor concentrates made from pooled plasma. Documents later revealed that some companies were slow to phase out older, unsafe stocks; lawsuits and settlements followed, but the human toll was enormous. In the 1990s, substandard practices in parts of China caused widespread hepatitis and HIV infections among donors.

Those episodes proved two truths: plasma products can transmit infection if oversight fails, and corporate decisions can prioritize short-term profits over long-term safety. Modern processing reduces these risks dramatically, but the risk can never be eliminated entirely — especially when profit incentives lead to compromised sourcing or lax screening.

The Staggering Math: How Little the Raw Material Cost Explains Sticker Prices

The money numbers are stark and morally jarring.

According to industry estimates reported by investigators, the global plasma industry was worth billions and projections suggested rapid growth. Specific drug prices amplify the outrage: IVIG treatments routinely run hundreds or thousands of dollars per dose. Factor replacement therapies for hemophilia — lifesaving for many patients — can reach astonishing annual price tags in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A simple back-of-the-envelope comparison reveals the scale of the markup. It takes roughly 14 plasma donations to supply the protein for a single dose of a factor therapy. If donors receive an average of $40 per donation, the raw plasma input for that dose costs on the order of $550. Even after accounting for processing, testing, packaging and logistics, industry pricing puts retail costs orders of magnitude higher than the material input would suggest. That gap translates into massive profits for manufacturers and crippling bills for patients, insurers and governments.

Global Dependency: Why Nations Buy U.S. Plasma

Many countries that forbid paid plasma in principle still rely on plasma from paid donors because domestic, altruistic supply cannot meet demand. For example, nations like Australia have imported large fractions of their plasma needs. China, Canada, Switzerland, Japan and parts of Europe also source plasma internationally.

This creates a moral paradox: countries that outlaw paid donation on ethical grounds end up importing products made from paid donors because their own supply is insufficient. The global shortage and the high demand for plasma-derived medicines — including during crises such as pandemics — fuel both international trade and opportunistic black markets. Investigations have documented the appearance of illicit plasma sales in places like Egypt, where bags have fetched extremely high prices when supply tightens.

The Black Market and the Collateral Damage

When regulated supply cannot meet demand, black markets flourish. Reports from multiple countries describe brokers who masquerade as relatives or middlemen to harvest blood for desperate families; others describe sellers who exploit hospital environments to obtain blood for payment. While these actors claim to “save lives,” they also prey on poverty and can bypass safeguards meant to protect both donor and recipient.

There is another, subtler collateral effect: the presence of nearby plasma centers has been associated in some studies with reduced demand for predatory payday loans. While paying donors can be seen as problematic, access to plasma centers may function as an informal relief valve for communities with few financial options. That tradeoff — cash now in exchange for potential health risk later — is precisely where public policy should intervene rather than leave decisions wholly to markets.

Accountability, transparency and paths to reform

The market forces are entrenched: wealthy companies, enormous global demand, and a supply chain anchored in poor or precarious populations. But there are realistic avenues for reform that do not require outlawing lifesaving medicines.

Regulatory and corporate reforms worth demanding

- Stronger, consistent screening — Require more thorough checks on repeat donors and mandate more frequent laboratory testing. If companies claim safety, they should be willing to finance heightened screening without cutting compensation.

- Transparent accounting — Manufacturers should disclose production and processing costs alongside retail pricing. When public health depends on these products, secrecy about margins is unacceptable.

- Fair compensation tied to safety — If donors are a critical resource, companies should invest a meaningful fraction of revenue into donor health, follow-up care and longer recovery periods, rather than skim profits.

- Public investment in alternatives — Governments can fund recombinant and synthetic alternatives to plasma-derived proteins, reducing dependence on human donations and insulating patients from volatility in the donor market.

- International coordination — Donor sourcing and product safety are global problems. Cross-border standards and sharing of best practices could limit exploitation and reduce the pressure on low-income donors.

- Support for donor communities — Rather than treating donors as raw material, public and private sectors should provide social supports (job training, healthcare access) that reduce the economic compulsion to donate excessively.

Why Voluntary Giving Alone Won’t Solve the Problem

Some argue that the answer is simply to increase voluntary, unpaid donations. That is an admirable goal, but scale matters: current global demand far outstrips what purely altruistic programs deliver, especially for complex plasma-derived medicines. The shortfall will persist unless the industry and policymakers adopt a strategy that addresses both supply ethics and demand affordability.

Conclusion — The Moral Ledger that Governments and Corporations must Finally Balance

Plasma sits at an uneasy intersection of medicine, markets and morality. It saves lives, but as currently organized the blood plasma industry also concentrates profit in the hands of a few while outsourcing risk to the economically vulnerable. Donors donate for money; companies sell for margin; patients and public health systems shoulder the price. That arrangement should disturb us.

If society treats human biology as a simple commodity, then the poorest will always be the suppliers and the wealthiest the beneficiaries. That is not just an economic imbalance — it is an ethical choice we make collectively. Governments can legislate safer procurement standards, require transparency about pricing, invest in alternatives and fund social programs that reduce coerced donation. Companies can accept greater responsibility for donor welfare rather than optimize purely for throughput.

This is not a call to doom the industry that produces essential medicines. It is a call to demand accountability: full disclosure, humane practices, and policy that protects the vulnerable rather than exploiting them. The business of blood must be transformed from a marketplace that quietly profits off precarity into a system that treats donors and patients with dignity — because the blood that keeps us alive should never be the currency of avoidable suffering.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Why is plasma so valuable to pharmaceutical companies?

Plasma is rich in proteins like antibodies, clotting factors, and albumin that cannot be synthetically manufactured. These proteins are essential for producing life-saving therapies for patients with immune deficiencies, hemophilia, and severe burns. Because demand is high and supply depends entirely on human donors, plasma has become a billion-dollar resource for pharmaceutical companies.

-

How much is the plasma industry worth globally?

The global plasma industry is valued at over $34 billion annually and continues to grow rapidly, driven by rising demand for plasma-derived medicines. Analysts project that the market could reach $60–80 billion within the next decade, making it one of the fastest-growing sectors in healthcare.

-

Is plasma donation safe for frequent donors?

Plasma donation is generally safe when done under regulated conditions, but frequent donations can lead to fatigue, low protein levels, and weakened immunity. In the U.S., donors are allowed to give plasma up to twice a week, which some experts say may put long-term strain on the body. Safety depends largely on how often a person donates and their overall health.

-

How much do plasma donors get paid in the U.S. and Europe?

In the U.S., plasma donors are typically paid $30–$60 per session, and frequent donors may earn up to $400–$800 per month. In contrast, most European countries prohibit paying for plasma donations due to ethical concerns, meaning donors usually volunteer without compensation.

-

Why does plasma cost thousands for patients but donors get so little?

Plasma therapies undergo an expensive process that includes collection, testing, purification, and pharmaceutical development. While donors receive small compensation, pharmaceutical companies profit by selling plasma-derived drugs at thousands of dollars per treatment. This gap raises ethical concerns about exploitation and fairness in the plasma economy.

-

What was the contaminated blood scandal?

The contaminated blood scandal refers to cases in the 1970s–1990s when thousands of patients worldwide were infected with HIV and Hepatitis C from unsafe plasma products. Much of the contaminated plasma came from high-risk paid donors, including prisoners. The scandal led to stricter regulations but left a lasting legacy of mistrust in the blood industry.

-

Should blood plasma be treated as a human right or a commodity?

This question remains debated. Advocates argue that plasma should be a human right because it is derived from the human body and used to save lives. However, in practice, it is treated as a commodity within a multibillion-dollar global market. The ethical challenge lies in balancing fair compensation for donors with the life-saving needs of patients.

Read More: Exploring the Future of Life and Technology

BioticsAI is more than just a breakthrough in medical technology—it represents a shift in how humanity cares for its most vulnerable lives before they even take their first breath. As AI continues to merge with healthcare, new doors are opening for safer pregnancies, early detection of complications, and more personalized maternal care.

If you’re curious about how technology is reshaping the future of healthcare and life sciences, read our article “BioticsAI: Humanity Meets Technology to Help Unborns”

The journey of BioticsAI reminds us that while machines may process data, the ultimate goal is deeply human: protecting life and nurturing hope.