- 3 February 2026

- No Comment

- 22

The Silent Cash Killer: Lessons from the Working Capital Trap

The Great Corporate Paradox: When Success Feels Like Failure

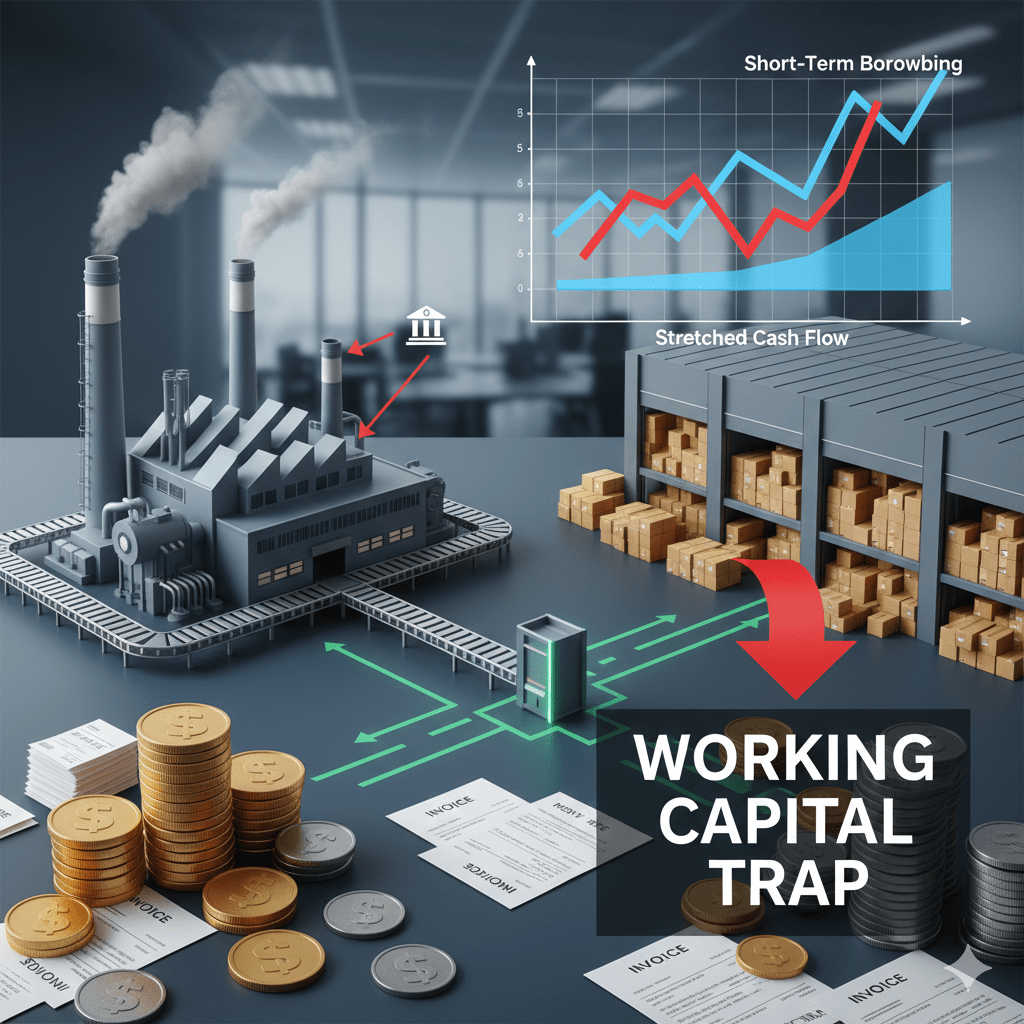

If we imagine walking into the busy corridors of a growing Pakistani enterprise. I’m sure we would see digital earnings board in the lobby that flashes a net profit in the billions. On paper, the company that is a titan of industry but behind the glass doors of the finance department, we might find the atmosphere being electric with tension. There is a possibility that CFO is on a conference call with a commercial bank, negotiating an extension on a credit line. The procurement team is responding to increasingly urgent calls from suppliers, and the human resources manager is quietly calculating if there is enough liquidity to meet the month’s payroll.

Actually, I am picturing the harsh reality of the Working Capital Trap. It is a financial paradox where a company can be “profitable” according to its income statement but can be “broke” according to its bank account.

In 2025, Pakistan’s corporate sector became a living laboratory for this phenomenon. Across almost every industry, from the heavy furnaces of cement plants to the intricate looms of textile mills, companies recorded impressive profits while at the same time raising concerns regarding short-term liquidity adequacy.

This trap emerges when a company’s fundamental resources are tied up in non-cash items. These are funds tied up in piles of unsold stock, trade receivables that take months to collect, prepayments to suppliers who are not very trusting, or government refunds that are stuck in bureaucratic limbo. This ensures that businesses are not able to turn their “paper profits” into the cash that they need to survive from day to day. Even the strongest revenue stream will not keep a business from being cash strapped if its working capital is poorly managed.

The Mechanics of the Trap: The 2025 Triple Squeeze

The mechanics of this trap become painfully clear when we examine the cash conversion cycle. This cycle measures the time it takes for every rupee invested in operations to return to the company. In 2025, the Pakistani corporate environment created a “triple squeeze” that decimated corporate liquidity.

The Inflationary Inventory Surge

As we are aware of the fact that the inventory costs surged due to historic inflation and global supply chain pressures. Companies were forced to hold more raw materials than usual to avoid production halts. This “Just-in-Case” strategy, while protecting production, but this move slowly pulled cash out of the business and turned it into physical stock, which then sat in warehouses and could not be used for daily operations.

The Government Refund Deadlock

If we talk about FBR’s behavior when its comes to refunding money to the taxpayers, patience seems to be the first requirement. As delays in government refunds, particularly Sales Tax and Income Tax refunds for exporters, trap significant sums of money. For many companies, these refunds represent a substantial portion of their working capital. When the government delays these payments, it effectively forces private companies to provide the state with interest-free loans, while those same companies must then borrow from banks at high rates to stay afloat.

The KIBOR Factor

Last but not the least, the cost of financing this trapped capital reached record highs. Short-term borrowings became a massive drain on resources, with KIBOR rates remaining high. The interest paid on these loans often consumed a significant portion of the operating profit, creating a cycle where companies were borrowing just to pay the interest on previous borrowings just like government of Pakistan. As per 2025-26 federal budget, out of the total PKR 17.6 trillion outlay, nearly 47% (around PKR 8.2 trillion) goes just to interest payments, while the Public Sector Development Program (PSDP) gets only PKR 1.28 trillion. In other words, for every 1 Rupee spent on roads, schools, and hospitals, over 6 Rupees is used to pay past debt.

Sector Analysis: The Profit-Cash Divergence

The Cement Sector: The Attock Cement Case Study

The cement sector provides one of the most dramatic illustrations of this trap. Attock Cement, a prominent market leader, posted a profit before tax of Rs. 2.8 billion in year ended June 2025. To a casual observer, the company appeared to be in a position of extreme strength. However, the cash flow statement revealed a different story. The company’s operating cash flow was negative Rs. 394 million.

The culprit was clear: inventory had increased by Rs. 1.1 billion, although trade receivables had reduced by Rs. 853 million but prepayments and advances increased by 330 million. To bridge this gap, Attock Cement had to raise Rs. 10.99 billion in short-term borrowings. Some might see Attock Cement’s Rs. 10.99 billion borrowing as a smart move, using the State Bank’s Export Refinance Facility (ERF) at low rates. But even cheap money can signal a deeper problem. Using ERF to cover operational gaps is risky. It comes with strict export performance targets. If the working capital tightens, if a shipment is delayed or a supplier stops supplying, the company could fail these targets. Then that supposedly cheap loan quickly turns into a high-interest burden. It feels like Attock Cement is not borrowing to grow. They are borrowing just to stay on track and keep their borrowing cheap.

Textiles: The Backbone Under Pressure

Textile companies which are considered the backbone of Pakistan’s export economy, faced even more acute challenges. Nishat (Chunian) Limited reported a negative operating cash flow of Rs. 5.26 billion. Despite consistent revenue generation, their finance costs alone amounted to Rs. 5.55 billion. This means that nearly every rupee earned from operations was immediately handed over to banks to cover interest.

Similarly, Artistic Denim faced a cash burn of Rs. 2.19 billion during the year. And the company secured an additional Rs. 3 billion in borrowing to cover this shortfall. This highlights the intensity of the trap in an industry dependent on long production and collection cycles. Even loss making entities were not immune; Idrees Textiles, which recorded losses of Rs. 398 million, had a staggering Rs. 2 billion trapped in receivables and stock, demonstrating how poor cash management can magnify financial stress regardless of whether a company is profitable or not.

Manufacturing Giants: Millat Tractors and the Inventory Bottleneck

Manufacturing giants like Millat Tractors proved that size and market dominance offer no immunity. Even with high revenue and consistent demand for agricultural machinery, the company’s inventory ballooned to Rs. 12.8 billion. And Millat Tractors relied on Rs. 14 billion in short term borrowings just to manage daily operations and bridge the gap between production costs and sales collections. This illustrates a critical lesson: even when sales are high, delayed collections and excess inventory can create a liquidity bottleneck that undermines the entire operational stability of a company.

FMCG and Food Processing: The National Foods Perspective

If we use National Foods as an example in FMCG sector, National Foods maintained steady profits, but its operational cash declined by approximately 5%. This must have been caused by increasing advances to suppliers and prepayments, which increased by 59%, and trade receivables, which grew by 50%. So the company had to liquidate its short term investments and arrange additional financing to maintain cash flow. Although profits remained positive, the actual access to cash was limited for the company, underscoring the vital difference between accounting performance and real world liquidity.

Why Financial Ratios are Not Neutral

Though financial ratios are helpful but often do not provide an accurate picture of the actual financial position of a firm in a fluctuating economy like that of Pakistan. A company may have a “Current Ratio” that looks good because it includes “Trade Receivables” as a current asset. But a receivable from a struggling power plant or a pending refund from the government is not the same thing as money in the bank.

In 2025, these differences became the main concern of auditors and analysts. A company’s profit margins may look good, but if its cash requirements for working capital increase significantly, then the actual amount of money available to finance the business may be very little. For instance, if a firm has a profit margin of 20% but its cash conversion cycle increases from 60 days to 120 days, then the firm is still likely to go bankrupt even if it is technically profitable.

The Human and Operational Cost

The human side of this data is a fascinating and often underappreciated story. Factory floors in Pakistan in 2025 were humming with activity, products lining warehouses, and sales teams continued to meet their targets. On the outside, the company seemed to be doing well. But on the inside, the story was one of never ending stress.

Finance departments were under constant pressure to manage cash flow. Suppliers were starting to call in their favors, demanding “cash on delivery” as they found themselves facing their own liquidity crises. This is a domino effect; when one large corporation finds itself facing a cash crisis, it means it has to pay its smaller suppliers late, who in turn have trouble paying their employees and their suppliers.

Strategic Escape Routes: Mastering the Cycle

Escaping the working capital trap requires a shift in management philosophy from “accounting for profit” to “managing for cash.”

1. Inventory Optimization

A disciplined approach to inventory management, from “just-in-case” to “just-in-time,” is required. A company holding Rs. 12.8 billion in inventory, as observed in Millat Tractors, is not a very safe approach in a high-interest rate environment. Lean inventory management, fueled by improved demand forecasting, can unlock billions of rupees of stuck cash.

2. Active Receivables Management

Trade debts need to be handled with a sense of urgency. Techniques such as “Factoring,” where the company sells its receivables at a slight discount in order to get immediate cash, can be of temporary relief. Although it may cut the profit margin slightly, the advantage of getting immediate cash may far outweigh the cost, especially when the rates of borrowing from banks are high.

3. Strategic Payables Management

It is equally important to manage payables. Arranging for extended payment terms with suppliers and providing small incentives or discounts for early payment from customers can assist in shortening the cash conversion cycle. It is all about striking a balance where cash enters the company sooner than it leaves.

The Student and Professional Perspective: A New Era of Analysis

As CA aspirants and finance professionals, the following are the takeaways from the year 2025. In your studies and professional life, the time has come for a change.

The Superiority of the Cash Flow Statement

While the Profit & Loss account is a measure of performance, the Cash Flow Statement is a measure of survival. It is essential that students are able to move beyond the Net Income and examine the “Changes in Working Capital” section. A huge rise in the receivables or inventory level is a cause for concern, irrespective of the rise in the sales.

Understanding the Cost of Capital

The Cash Conversion Cycle and KIBOR relationship has become a cornerstone of Pakistani corporate finance. It is imperative that practitioners are able to determine the “Liquidity Premium” that a company incurs when it does not manage its working capital effectively. In 2025, the liquidity premium was the difference between a successful business and a distressed one.

Conclusion: Cash is King, But Liquidity is the Kingdom

These small pieces of data from the corporate world in Pakistan in 2025 are a reminder of this fact: profitability without liquidity is but a dream. A company can be making billions, but if it doesn’t turn that profit into cash, it is susceptible to every economic shock.

Whether it is a profitable behemoth like Attock Cement, which needs to borrow Rs. 11 billion, or a company like Idrees Textiles, which is in the red and needs to borrow Rs. 2 billion just to stay afloat, the bottom line is the same. The working capital nightmare is a silent killer of corporate promise. The finance professional of the new age is no longer faced with the task of balancing the books. The task is to make sure that the books reflect a business that is not only successful on paper but also resilient in the real world. In a world where liquidity is the real king, only those who can manage their cash flow will truly thrive.

Author: Emaan Ghous

Program: CFAP Student (ICAP)

This article is submitted by author as part of the Nashfact National Writing Competition. Views expressed are the author’s own.